The Fur Trade

The French in North America quickly realized that this continent had riches that they could exploit via the fur trade. For the fur trade network to function, they depended on Native people, who trapped the animals and exchanged the furs and skins for European-produced merchandise. The relationship between the French and Natives was complex as well as economically and culturally important.

At first, the French required that the Native people bring their furs to Montreal. But in the North American fur trade, the French had competition. The British colonies also carried out trade for furs and skins with the Native people, so the French needed to create favorable trading conditions for the Natives: ease of access to trade, high-quality trade goods, and generous prices for the furs.

To try to beat out their British competition and make access to the trade easier for their Native trading partners, France eventually gave traders permission to travel far from Montreal into the region of the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River. There, they could trade directly with the Native people in trading posts in the pays d’en haut (the “upper country”–French term for the Great Lakes area) and the pays des Illinois (the Mississippi Valley area, literally the country of the Illinois Native tribes).

The government attempted to exercise control over the trade by granting licenses to trade, known as congés, to a limited number of people. However, numerous men set out without licenses to try to benefit from this lucrative trade; they were known as coureurs des bois (“runners of the woods”).

This trade between the French/Canadian traders and the Native people lasted more than 150 years, from the mid-1600s to the early 1800s. Even after the mid-1700s, when this region was no longer governed by the French, the valuable relationships, trade routes, and business practices established by the earlier French traders subsisted, and the fur trade was a primary factor in the region’s economic development.

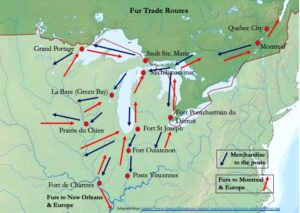

Over this entire period of time, the basic route of trade involved transporting manufactured goods from the Atlantic coast to Montreal and then inland, and transporting furs from the pays d’en haut and the pays des Illinois back to the ocean via the St. Lawrence. When France had established New Orleans as a viable port on the Gulf of Mexico in the early eighteenth century, furs–particularly from the Mississippi Valley–also moved to Europe by this southern route.

Observing the outline of this route, we can see why the inland river system was crucial: this was the method of transportation for manufactured goods moving in and furs moving out. Birchbark canoes and flat-bottomed boats called “bateaux” transported bales and barrels across lakes and down rivers large and small.

To facilitate the trade, the French established trading posts, some that were larger and more permanent and others that were smaller and often temporary. The posts were located on bodies of water, almost always near Native villages. These locations allowed the French to benefit from the presence of a community of Native partners. Larger posts had fortifications and usually a small military presence, as well as some religious representation in the person of a priest, though at smaller sites the priest might be present only sporadically.

The timeline of the trade route, broadly presented, is as follows:

1) European merchandise arrived by ship at Montreal (or other North American ports).

2) In spring, when ice melted from the rivers, the merchandise was transported in large canoes from Montreal to several major trading posts like Michilimackinac—in northern Michigan—or Detroit or Grand Portage on Lake Superior. There, the traders divided up the merchandise into smaller packs, creating bales of items like cloth or putting other goods into different-sized barrels.

3) Men whom we know as voyageurs left the major trading posts in summer, traveling by canoe with these bales and barrels of merchandise to meet up with the Native people in their villages, near smaller forts and trading posts. We know about some of these posts, like Fort St. Joseph, Fort Ouiatenon, Prairie du Chien, La Baye (Green Bay), or Fort Miami, while other smaller posts have completely disappeared today.

4) During winter, the Native people traded their furs and skins for the manufactured goods they wanted. As we will see below, the goods they sought to purchase served a variety of functions, ranging from useful items like metal pots, knives and axes or cloth and blankets to items of personal decoration like beads or earrings.

5) In the spring, the voyageurs left the small posts or villages to return to the larger trading posts with the furs they had acquired. At these sites, like Michilimackinac or Detroit or Grand Portage, the traders aggregated the furs into packs and shipped the packs in large canoes back to Montreal.

6) Finally, the furs and skins left Montreal for Europe where they would be sold. Starting in the early eighteenth century, furs and skins were also shipped south on the Mississippi River to the French colony of New Orleans and then to Europe.

Many inland water routes served as ways by which the Native traders could bring the pelts to their French counterparts. The following map suggests the general directions in which the trade was carried out:

Furs and Trade Goods

What did the voyageurs and traders exchange for furs? Some of the goods the Native people received in exchange for their furs were primarily for practical use: for example, knives, axes, kettles, blankets, cloth, clothing, combs, gunpowder and shot or musket balls for their guns.

Other items that they received from the French traders were used for personal decoration: for example, ribbon, brooches, earrings, bracelets, vermillion (a red pigment to decorate the body), or small bells.

What were the furs and skins—les pelleteries, or pelts—that the Natives brought to trade for this merchandise?

The most important and the most in demand was beaver. In Europe, beaver fur was used to make felt for hats, but the European beaver population had become depleted. This new source of beaver pelts filled an established economic niche and the trade was, at first, very lucrative.

In the Great Lakes and Mississippi River areas, there were many other animals whose fur was also in demand: fox, bear, otter, mink, marten, muskrat, raccoon (called chat sauvage or “wild cat” by the French), and even bison. In addition, many deerskins were traded for the merchandise brought by the traders.

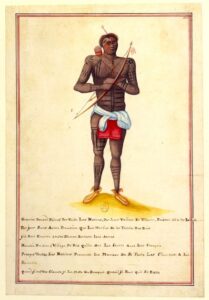

The voyageurs and traders who lived in le pays d’en haut—the upper country, as the French called the Great Lakes area—or le pays des Illinois—the Mississippi Valley—needed to adapt to conditions in this region, where there were no large towns and few European-style settlements. It was essential to learn from the Native people who had long lived here, and as a consequence they adopted many items invented by the Natives which worked well for life in this region. For example, they made extensive use of the birchbark canoe, which was light but sturdy, and worked much better than a European boat on the rivers on which they traveled.

They adopted items of clothing as well, including moccasins of deerskin and breechcloths with leggings, all of which were much better adapted than trousers and hard-soled shoes for life in the forest.

They also made use of the mokock (a word originating in the Ojibwe language), a kind of bowl or bucket made of birchbark used for storage and transport, as well as the apaiquoy (a word originating in Algonquian languages), which indicated strips of birchbark that served as a portable shelter.

Visit Fur Trade Sites

Visitors can learn first-hand about the fur trade at several sites in the French Heritage Corridor. In Illinois, you can visit the Isle à la Cache museum. In Michigan, Colonial Michilimackinac immerses visitors in eighteenth-century life in this important fort and fur trading center. Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin hosts the Fur Trade Museum and in northwest Indiana visitors can tour the Joseph Bailly Homestead at the Indiana Dunes National Park. And farther north, Grand Portage National Monument helps visitors understand the important relationship between French and other European traders and the Anishnaabe Native people. Consult the French Heritage Corridor’s interactive map to plan your visit.

For immersive experiences, you can attend a rendezvous event, where reenactors recreate the experience of traders and Native people coming together at fur trade posts. The Feast of the Hunters’ Moon in Indiana and the Fort de Chartres Rendez-vous in Illinois are just two examples.