More French Heritage

There are many stories of French heritage to tell. While some zoom in on individuals who influenced the evolution of the area known as the French Heritage Corridor, others involve groups that played important roles in establishing and maintaining the area’s French heritage. The links on the French Heritage Corridor’s interactive map will help you to discover the variety of places that preserve this heritage, from historical sites to museums, cultural markers, Native heritage sites, and more.

As the earliest French speakers arrived, they encountered a variety of Native peoples with diverse and complex cultures. French speakers also found variety in terrain, climate, and agricultural opportunities. However, the territory was also united by an extensive system of inland waterways, from the northern Great Lakes to the Mississippi River valley, with river systems draining from north, east and west, serving as the highways by which the French entered the region and which facilitated the transport of goods and furs.

Here, our approach to exploring the continued French heritage of the Corridor is organized state by state, but the region is united by waterways and by its French heritage. What follows here is just a brief introduction of the French roots of each of the states: there is much more to explore.

Illinois’ French Heritage

The first non-Indigenous person to set up business in what is now Chicago was Jean Baptiste Point DuSable. A French speaker of African descent, Point DuSable is believed to have been born in what is now Haiti, though much about his early life is unknown. (The book by Marc Rosier called Chicago’s Authentic Founder, referenced on the “Further Exploration” page, is an exhaustive study of DuSable, what we know and what we don’t know about his life.)

Outside Chicago, the Village of Bourbonnais and the surrounding area along the Kankakee and Iroquois Rivers boasts a French-Canadian heritage. Fur trader Noel LeVasseur and the brothers Antoine and Francois Bourbonnais, Sr., entered the Kankakee and Iroquois River Valleys as fur traders for the American Fur Company in the 1820s. In 1837, LeVasseur returned to his native Quebec Province to recruit French-Canadians to settle in northeastern Illinois when the Potawatomi were compelled to move west of the Mississippi River. Beginning in 1846, a considerable number of families arrived. Today the portion of Interstate 57 in the area has been designated the French-Canadian Heritage Corridor in recognition of this French-speaking heritage.

The French built several early short-lived forts along the Illinois River, including Fort Crèvecoeur at the site of today’s Peoria, Illinois. Another long-lasting community was formed near where the Kaskaskia River enters the Mississippi. A settlement of habitants, priests, and Natives—the Kaskaskia people—developed on the east side of the Mississippi River. The settlement was strengthened by the addition of the Fort de Chartres, first a wooden structure begun in 1719 and finally a stone fort begun in the 1750s. Today, historic buildings are still in place in the town of Prairie du Rocher and the reconstructed fort is open to visitors. Explore this region of le pays des Illinois at this site. Within the French Colonial Historic District is the home of Illinois’ first lieutenant governor, trader Pierre Ménard, as well as the village of Kaskaskia.

Indiana’s French Heritage

The town of Vincennes, Indiana traces its origins to the French fort and trading post formed in 1718 whose first commander was Jean-Baptiste de Bissot, sieur de Vincennes. Still today you can see the Old French House (built around 1806 by Michel Brouillet) and the Old Cathedral—the Basilica of St. Francis Xavier—whose parish records date to 1749. The buildings of French Fort Ouiatenon, founded in on the Wabash River in the first decades of the eighteenth century, no longer exist, but the site is part of the Ouiatenon Preserve. Further east, the town of Vevey, Indiana, on the Ohio River, was settled in 1802 by Swiss immigrants who intended to cultivate grapes and produce wine.

Iowa’s French Heritage

Julien Dubuque’s legacy is remembered in the Mississippi River city named for him. Born in Quebec in 1762, he came to what is now Iowa to mine lead. He wished to exploit the lead mines on both sides of the Mississippi, and in 1788, in Prairie du Chien, signed an agreement with the Fox tribe that would permit him to work the mines. He also secured the permission of the Spanish governor of Louisiana since, at that time, land west of the Mississippi River was Spanish territory.

A group of idealist Utopian communitarians from France, under the leadership of Etienne Cabet, came to the United States in the 1850s. Cabet envisioned the formation of this community as “un voyage en Icarie,” and the members called themselves “icariens.” They came first to Texas but then moved north to Nauvoo, Illinois and, later, to near Corning, Iowa, where their experiment in communitarian living ended in the 1890s.

Michigan’s French Heritage

From north to south and east to west, French heritage is present in the state of Michigan. The French origins of Detroit—founded by Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac in 1701—and Mackinac are well known. Fort Michilimackinac was founded by the French and this site at the Straits of Mackinac remained one of the principal centers for the fur trade through the nineteenth century.

Sault Ste. Marie, on the St. Mary’s River between Lake Superior and Lake Huron, was an early French settlement, and the French heritage of the River Raisin area in southeast Michigan is visible today in several remaining structures dating to the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The Fort St. Joseph archaeological project in southwest Michigan reveals details about daily life at the eighteenth-century French fort.

Follow this link to find much more information about Michigan’s French heritage as well as further links allowing you to explore in depth.

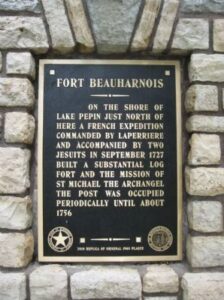

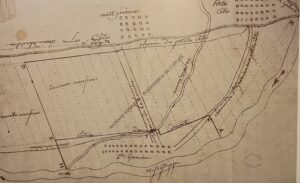

Minnesota’s French Heritage

Water and waterways define the region today known as Minnesota. Minnesota is and has always been a Native place as well. There are currently eleven sovereign Tribal Nations in Minnesota. In the past, these Indigenous peoples, including the Dakota, the Ojibwe, and their ancestors created a vast network of water (canoe) trails, linked by carrying places or portages. When the French arrived beginning in the seventeenth century, learning, quite literally, to navigate the natural and cultural nuances of this vast waterscape was key to the establishment of a permanent French presence in the region (Birk 1994; Gilman 1982). The beginnings of a French heritage in Minnesota were established on the Lake Superior/Grand Portage/the Border Route, along the Upper Mississippi River, in the Minnesota River Valley and braided through the Red River Oxcart Trail system… Click here to read more.

Missouri’s French Heritage

French heritage runs deep here. St. Louis’s French heritage is well known: it was settled in the 1760s by French residents of the Illinois Country seeking to distance themselves from British rule by moving across the Mississippi River, and named after the French king Louis IX, Saint Louis. It grew as a commercial center and fur trade post with perhaps its most well-known early citizens being Pierre Laclède Liguest and Auguste Chouteau.

A bit further south, the town of Ste. Genevieve was established on the Mississippi even earlier, in the mid-1700s, and has retained its French character in many ways. Many of its historic French homes have been lovingly preserved, presenting excellent examples of the traditional building styles of La Nouvelle France called poteau sur solle (post on sill) and poteau en terre (post in ground). And the French tradition of village residents together farming a common field was an early practice in Ste. Genevieve.

Another Missouri community with deep French roots is Old Mines (Vieille Mine), where lead mining began in the early decades of the 1700s. The French-speaking population here continued their use of the French language long after the territory was ceded by France, leading to the development of what is called “Paw-Paw French,” a distinct dialect. You can learn more about “paw-paw French” here and hear Midwest Creole music performed by Dennis Stroughmatt and L’Esprit Créole here.

Wisconsin’s French Heritage

During the period up to 1763, the French established forts and trading posts throughout Wisconsin. Green Bay, known as “La Baye,” began as a trading post established by Jean Nicolet in 1634, and a Jesuit mission was founded there later that century. The area around La Pointe, just off Chequamegon Bay on Lake Superior, was the site of a fur trade post and mission established around 1660. At Trempealeau a small post was established as early as 1685.

The site of Prairie du Chien was known to Europeans from June 17, 1673, when the expedition of Marquette and Jolliet arrived at the mouth of the Wisconsin River. The fur trade was carried out here until the nineteenth century, with French-speaking traders like Michel Brisbois and Joseph Rolette playing leading roles even after the territory became British and then American. Link: Prairie du Chien Historical Society

Fur trader and businessman Solomon Juneau, born in Quebec in 1793, was instrumental in the development of Milwaukee. And immigrants from the French-speaking region of Belgium called Wallonia settled near Green Bay in the mid-nineteenth century.

Click here to see an extensive list of reference works on Wisconsin’s French History

This is just a hint of the rich history that exists within the French Heritage Corridor. There is more to learn about each of the people and groups described here, and there are many more places, groups, and people whose history and cultural contributions can be explored.

A good place to start is with the many links that you can access through the interactive map on the French Heritage Corridor site. Explorez!