French Heritage: The Beginning

We can trace the beginnings of French heritage in North America to the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, when France, like other European powers, sent explorers, traders, and settlers to the continent hoping to exploit the riches they were confident they would find here.

In the sixteenth century, the French wished to increase trade with China and the rest of Asia, but the land route from France was difficult and risky. Might there be a quicker route through North America? The French also wanted to compete with other European powers such as Spain, who had begun extracting wealth from newly-conquered lands in South America. With an expansion of French power in mind, the French king sent men to explore the northern part of North America, starting with Jacques Cartier. Cartier entered the St. Lawrence River in 1534, 1535, and 1541, but returned home without establishing settlements in North America. However, the availability of furs quickly proved to be a tempting source of wealth, motivating the French crown and merchants to expand their presence on the continent.

Settlements Begin

In 1603 and the years following, Samuel de Champlain returned to the continent, where he and his companions had been tasked with establishing permanent trading sites. After several failed attempts to set up posts on the Atlantic coast, Champlain returned to the site that is today Quebec City and, with around 30 settlers, established the “Habitation de Québec.” They created alliances with the Native peoples of the region, Montagnais, Algonquins, and Hurons, aiming at further developing the fur trade relationship with these groups as well as others farther inland. The trading post of Trois-Rivières was established in 1634. Eight years later the town of Montreal, called “Ville-Marie” at the time, was founded on an island in the St. Lawrence. Though the initial goal of its founders was to form a missionary city where the Indigenous could be converted to Catholicism, the settlement soon lost its primary religious function and became a crucial part of the ever-growing fur trade.

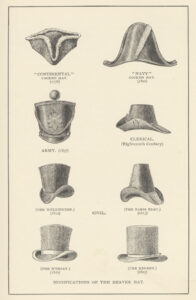

While the French still hoped to find a river route to the Pacific through North America, it was the fur trade that became the most important part of the French efforts to profit from their presence on the continent. They relied on Indigenous people to supply the furs in exchange for manufactured goods imported from Europe. Most valuable was the beaver, whose underfur was processed into felt for hats, but many other animal furs and skins were also traded for a wide variety of goods including metal products, cloth, silver jewelry, and beads.

The French also sought to take advantage of the mineral resources of North America, hoping to reproduce the extraction of mineral wealth from which Spain had profited in its South American colonies. Although there were no signs of gold mines in the St. Lawrence River valley nor the areas to the south and west into which the French were increasingly moving, they did learn that there were deposits of lead, perhaps copper, and other minerals in this territory, and periodically efforts were made to exploit this resource.

Into the Continent’s Interior

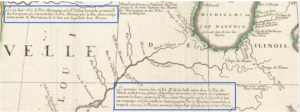

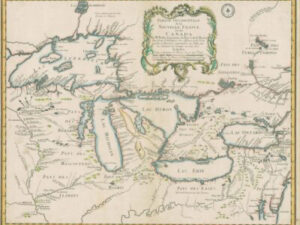

From the small settlements of Quebec City, Trois-Rivières, and Montreal, the French continued, in the mid-1600s, to send men to explore toward the west and south, heading deeper into the region of the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River. Gradually, they established trading posts and forts as well as religious missions. The names of these French explorers are familiar. Louis Jolliet and Father Jacques Marquette were the first Europeans to travel down the Mississippi River, in 1673. Jean Nicolet traveled through the area that is today Wisconsin, Michigan, and Minnesota. Pierre-Esprit Radisson and Médard Chouart des Groseillers traveled throughout the Lake Superior area. René-Robert Cavelier de la Salle was the first Frenchman to follow the Mississippi River to its mouth at the Gulf of Mexico, planting a flag and plaque that claimed the territory for France in the name of Louis XIV on April 9, 1682; henceforth, the French would call this southern part of La Nouvelle France “Louisiana.” Ultimately, the French would call the region around the Great Lakes le pays d’en haut (the upper country), and the area south of the Great Lakes closer to the Mississippi le pays des Illinois (the country of the Illinois) after the Native people they encountered there.

Some of the westward expeditions were sponsored by the crown or officially-sanctioned investment groups, but other Frenchmen set out on their own without official permission; they were known as coureurs des bois. Many expeditions included Jesuit or Recollect priests, who sought to establish missions in order to convert the Native people to Christianity.

Native Partners

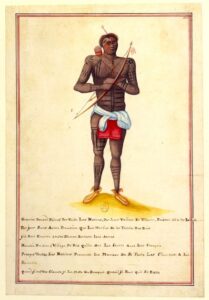

Near the St. Lawrence River settlements like Montreal and Quebec City, the Indigenous trade partners of the French were Montagnais, Algonquins, Hurons, and, to some extent, Iroquois people. Among the tribes that the French encountered as they moved westward and southward were the Odawa, the Ojibwe, the Potawatomi, the Illinois, the Miami, the Shawnee, the Winnebago, the Hurons, the Meskwaki, the Dakota, and the Wea. Native people played a crucial role in the survival of the French. First, the Indigenous people knew how to survive in this environment; the French had much to learn from them regarding food, clothing, transport, and shelter as well as the terrain and its challenges and opportunities. Second, of course, the Native people furnished the furs that the French wished to export. And finally, the Native people could help the French become integrated into the complex trading systems that already existed among groups of Natives.

Many early observations of the region come from the correspondence of the Jesuits who traveled and lived here, records known today as the “Jesuit Relations.” Letters from French military officers to their commanders in France also record the activities and observations of the French in the pays d’en haut and the Illinois country. Some local or parish records are preserved in state or city archives.

In addition, archeological investigations of sites like Fort de Chartres in Illinois or Fort St. Joseph in Michigan can teach us much about the everyday world of that time by analyzing the material record that remains.

Since the written records from that time, however, were produced by the French, these early views of the region and its Native people reflect a European perspective and interpretation. To gain a more complete view, we must seek the Native perspective as well. We can do that by consulting sites that provide the history of Native-European encounter from the Native point of view like the Myaamia (Miami) community blog, available here , or the Citizen Potawatomi Nation’s Cultural Heritage Center here.

Gradually, the French set up small forts, trading posts, and missions scattered throughout the Great Lakes and Mississippi Valley region. The main function of a large number of these places was to facilitate the fur trade and, in some spots, the extraction of lead or other minerals. Nonetheless, there were habitants–as ordinary settlers were called–who worked as farmers and artisans, creating a more mixed economy, commercial and agricultural, and implanting French language and customs in the small communities. However, the number of settlers remained small. By 1760 there were probably only about 9,000 French-speaking people—some soldiers, some fur traders, some habitants–living in this part of La Nouvelle France.

French Presence Remains

French speakers influenced the evolution of this region in multiple ways. Some of the small French communities became towns and cities, whose names are tangible signs of that French heritage: among them we find Detroit, Sault Ste. Marie, St. Louis, Prairie du Chien, Ste. Genevieve, or Vincennes.

And even after France officially ceded its North American territories, French presence remained strong in the French Heritage Corridor region. Although some French forts were closed, and others became British and then American after the American Revolution, many habitants remained, as did French-speaking fur traders and businessmen. They played a key economic role as first British and then United States interests increasingly moved into this territory. The French and French-Canadians proved themselves capable of navigating among multiple partners—British, French, Spanish, U.S., Native—in the complex world that was taking shape.

Today we recognize individual French speakers like Pierre Ménard, Jean Baptiste Point DuSable, Felix Vallé, Auguste Chouteau, Michel Brisbois, Julien Dubuque, Father Louis Hennepin, and many more, as central players in the history of this region in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, but we must also acknowledge the activities of many other French speakers, groups and individuals, women and men, in the early recorded history of the French Heritage Corridor’s region. Their presence, bringing with it the French language, customs, culture, and religion, added to the rich historical and cultural mix that characterizes this region. That French heritage is kept alive today by community groups, historical societies, cultural events, museums, and historical sites throughout the French Heritage Corridor. The French Heritage Corridor interactive map (https://frenchheritagesociety.org/fhc2/interactive-map/) presents links that will help visitors discover sites from throughout the Corridor and invites them to immerse themselves in this rich history.